Mahayana Buddhism is known as the Great Vehicle. It is the heart of the Buddha’s teachings, combining the profound insight of emptiness with the vast motivation of compassion.

Table of Contents

Mahayana Buddhism Summary Details

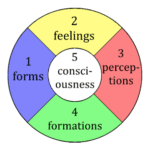

| Entity | Description |

|---|---|

| Mahayana Buddhism | A branch of Buddhism emphasizing the path of the Bodhisattva, a being who strives to achieve enlightenment for the benefit of all beings. |

| Theravada Buddhism | Another major branch of Buddhism focusing on individual liberation through following the teachings of the Buddha. |

| Bodhisattva | An enlightened being who postpones their own nirvana to help others achieve enlightenment. |

| Buddha | A fully enlightened being who has achieved liberation from suffering and the cycle of rebirth. |

| Nirvana | The state of liberation from suffering and the cycle of rebirth, the ultimate goal of Buddhist practice. |

| Six Perfections | Generosity, ethical conduct, patience, joyous effort, mindful concentration, and wisdom, cultivated by Bodhisattvas on their path to enlightenment. |

| Emptiness (Shunyata) | The concept of the ultimate nature of reality, which is seen as empty of inherent self-existence. |

| Skilful Means | The wisdom to adapt one’s teaching and actions to best suit the needs and understanding of different individuals. |

| Mahayana Sutras | Buddhist scriptures specific to the Mahayana tradition, emphasizing the Bodhisattva path and Mahayana concepts. |

Relationships

| Relationship | Description |

|---|---|

| Distinct from | While both share core Buddhist principles, Mahayana emphasizes the Bodhisattva path and specific Mahayana concepts, contrasting with Theravada’s focus on individual monastic practice and achieving nirvana for oneself. |

| Embodied by | The Bodhisattva ideal is central to Mahayana Buddhism, highlighting the qualities of compassion and the dedication to helping others achieve enlightenment. |

| Aspires to | The ultimate goal of the Mahayana path is to achieve Buddhahood for the benefit of all beings. |

| Leads to | Nirvana remains the ultimate goal in Mahayana, albeit achieved through the Bodhisattva path and helping others reach enlightenment. |

| Cultivates | These qualities are essential aspects of a Bodhisattva’s journey, reflecting their dedication to helping others and progressing towards enlightenment. |

| Emphasizes | The concept of emptiness is a core Mahayana philosophical concept, challenging the notion of inherent self-existence in all phenomena. |

| Employs | Similar to Vajrayana, Mahayana emphasizes skillful means, adapting teachings and practices to best reach diverse individuals. |

| Based on | These scriptures form the textual foundation of Mahayana Buddhism, containing teachings and stories specific to the Mahayana tradition. |

Mahayana Buddhism

Mahayana Buddhism, often regarded as the “Great Vehicle,” stands as a profound and influential tradition within Buddhism. In this comprehensive exploration, we will delve into the intricate facets of Mahayana Buddhism, examining its origins, key teachings, practices, and the profound impact it has had on the spiritual landscape throughout history and across diverse cultures.

Origin of Mahayana Buddhism

Mahayana Buddhism, with its roots in India during the early centuries CE, marked a departure from the earlier form of Buddhism known as Theravada. The Mahayana tradition introduced a radical shift in perspective, emphasizing the universal potential for enlightenment and promoting the altruistic aspiration of the Bodhisattva to attain

Buddhahood for the benefit of all sentient beings.

As Buddhism spread, Mahayana gained prominence in various regions, adapting to different cultural contexts while retaining its core principles. The diversity within Mahayana Buddhism reflects its ability to resonate with a wide range of practitioners across time and geography.

Bodhicitta

Bodhicitta means Awakened Heart. It’s the heart that longs for awakening into reality.

The Bodhicitta is considered to be the most rare and the most precious thing in all of spirituality, in all of Buddhism. Entering the Mahayana Path, one aspires to bodhicitta, fully engaging in the bodhicitta. Bodhicitta is the driving force of the bodhisattva’s journey.

Bodhicitta has relative and absolute aspects. The relative has more to do with compassion for the suffering of sentient beings, and the absolute has more to do with the longing for reality, the union beyond the dualistic self with the absolute.

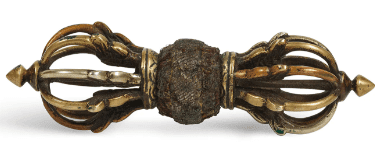

Bodhicitta is also essential for practicing the Vajrayana without the proper motivation. It’s the fuel that drives one through the rigors of the Vajrayana. The almost overwhelming power and intensity that genuine Vajrayana practice is and can be. A practitioner has to have the desire to genuinely liberate beings otherwise to negative consequences can occur.

One, nothing happens and it’s simply a waste of time. Two, the ego takes over and becomes monstrous using the Vajrayana tools of power and visualization. Three, the person goes insane.

Bodhisattva

The bodhisattva is closely connected to the bodhicitta. Obviously, it means awakening being. It’s the person who is traveling the path. The Buddha traveled the bodhisattva patH, and it apparently took thousands and thousands of lifetimes. The bodhisattva path is extremely difficult obviously.

It’s critical to maintain a very sincere and strong aspiration and motivation. This connects to the karmic flow. The bodhisattva uses the karmic framework in order to overcome the ordinary karma of self-preservation. They make aspirations to be a great bodhisattva, to live for the benefit of others, to seek wisdom. They make those aspirations over and over and over to attain Buddhahood for the benefit of the world. By making those aspirations as the front and center aspect of one’s being, it affects the karma. It creates the karma.

It creates what’s called merit to accumulations here. That merit becomes part of the fuel helping one to move towards enlightenment. In a sense you could say bodhicitta is the real fuel and merit is a part of that. You could also say that merit is somewhat of a compass by continually making those aspirations. When a person is reborn, when a being is reborn, then they move towards that automatically because they’ve trained their mind karmically. That is what they want to do, what they intend to do. That’s how the bodhisattva continues to find the path of Dharma for thousands and thousands of lives.

Bhumis: Bodhisattva Levels

At the heart of Mahayana Buddhism lies the Bodhisattva path, a distinctive feature that sets it apart from other Buddhist traditions. The Bodhisattva, driven by compassion, commits to achieving enlightenment not solely for personal liberation but to alleviate the suffering of all sentient beings.

The Bodhisattva path is structured into different levels, called bhumis, each representing a stage of spiritual development. These levels serve as a guide for practitioners on their journey towards Buddhahood and compassionate living.

Each Bodhisattva level is a transformative stage, challenging practitioners to cultivate virtues, overcome obstacles, and deepen their understanding of the interconnected nature of existence.

- Joyous

- Stainless

- Light Maker

- Radiant Prajna

- Hard to Overcome

- Manifest

- Far Gone

- Immutable

- Great Prajna

- Cloud of Dharma

Prajnaparamita

The Mahayana path is most strongly connected with the second turning of the wheel of Dharma, the turning on Prajnaparmita and Shunyata, or emptiness. The third turning on Buddha nature or Tathagata-garbha is also a Mahayana teaching, but it’s generally less emphasized. It gains prominence in the Vajrayana.

The second turning is the explanation of reality as explained in the Madhyamaka, which we get to a bit later in this article. With the second turning the bodhisattva travels the path of Madhyamaka, uses the study, and so forth.

The meditation is direct meditation on the nature of reality. The reason it’s called empty is because reality appears to be empty of fixed ideas and fixed substances from the point of view of relative mind. The absolute even appears empty from the point of view of the relative mind.

From the point of view of the awakened mind, reality is not empty. It is the Buddha nature. It is the Tathagatagarbha. It manifests in the form of wisdom and the form of Buddhas. The Buddha’s guide beings out of the suffering of conditioned existence and into liberation.

LOJONG

Lojong, the mind training by Atisha. The Lojong is seven categories of slogans, breaking out into 51 separate slogans. They have to do with training the mind to seek wisdom and to always act for the benefit of others.

Slogans such as “Rest in the Nature of the alya, the essence of mind,” “in Post-meditation be a Child of Illusion,” “Don’t Complain,” “Don’t malign others” and so forth guide the Mahayana practitioner toward enlightenment.

Madhyamika: The Middle Way

The Madhyamika school, founded by the philosopher Nagarjuna, plays a pivotal role in Mahayana thought. Nagarjuna emphasized the “Middle Way,” teaching the understanding of emptiness (shunyata) as a key to liberation. This philosophical approach encourages practitioners to transcend binary thinking and find a balanced perspective.

Nagarjuna’s teachings on the Middle Way are not only a profound exploration of the nature of reality but also a practical guide for navigating the complexities of life with wisdom and equanimity.

See this deep dive on Madhyamika logics.

Madhyamaka, or Uma in Tibetan, means middle way. It’s a classic tenet of the Mahayana and spans a broad set of philosophical approaches to reality extending into Vajrayana theory as well. The central channel of the subtle body is called the Uma. It’s the middle way between the two extremes of eternalism and nihilism.

More conventionally, Madhyamaka is a set of logical processes that overcome fixed notions of reality. It’s strongly associated with the Prasangika school of emptiness, and the rangtong, empty of self, philosophy about reality.

Things are not as they appear.

The Buddha

Nor are they otherwise.

There are hundreds of such logics, many of them created by the great master Chandrakirti, but an easy example is what’s called the one and the many. Conventionally we believe that if we think of a thing, we think of it as singular.

For example, a table. But the table is made out of a top, the legs, the screws that hold together, the paint or varnish on the table, and a number of boards that make it up. So a table is both one thing as a table and many things as the sum of its parts.

But there’s a principle of logic called the identity principle. A thing can only be what it is. It is its own identity, and it’s singular. Therefore a table does not truly exist. It only exists as an object in the mind, as the sum of the parts. Nothing can be two different things. Nothing can be one thing and simultaneously be many things as an absolute reality.

Of course, it functions as a table and no one denies that. That would be insane. However, when thoroughly analyzed you can’t find the table in any of the parts. It is only the sum of the parts. So at what point when dismantling the table does it cease to be a table? And if so, is the table in that last part that was taken away?

Of course, the answer is there’s no particular point at which it ceases to be a table because it never was really a table in a true sense.

Four Extremes

At any rate, the core element of Madhyamaka teachings is freedom from the four extremes. The four extremes are eternalism, nihilism, both, and neither.

Eternalism means that things exist in and of themselves and they exist forever. Or that there is a self that exists forever. Or a God that exists forever unchanging as some sort of physical or identity-based entity.

Nihilism is saying that nothing is sustained and that cessation extends throughout all time and space. It is in everything, hence all things are meaningless. So it is somewhat a view of darkness and can get progressively darker as the lack of meaning takes over.

‘Both existence and nonexistence’ and ‘neither existence nor nonexistence’ are more subtle doctrines. These are legitimate spiritual doctrines in other traditions.

BOTH means that things both exist and do not exist at the same time. But this doesn’t even make any sense. Logically, the two refute each other. So what’s the point of having such a view?

The fourth is phenomena neither exist nor do they not exist. This is the most difficult one because it sounds compelling. You can say they do not exist because you can’t prove that they exist using the one and the many and other such arguments. However, phenomena appear because the table is there and it functions in our relative reality. So it’s very compelling to say yes things neither exist nor do nor do they not exist.

The problem with this is it is a conceptual position. It is a way of framing the world as a thought, as a concept. To get beyond the conceptual, we need to overcome this last most subtle way of approaching it. We want to arrive at NO CONCEPT whatsoever. It’s merely direct experience.

Hence the middle way between the four extremes.

Prajnaparamita: The Perfection of Wisdom

The Prajnaparamita Sutras form the cornerstone of Mahayana Buddhist literature, providing deep insights into the nature of reality and the path to enlightenment. These scriptures emphasize the concept of emptiness and the perfection of wisdom, encouraging practitioners to transcend conventional views and concepts.

The Prajnaparamita teachings challenge individuals to go beyond the limitations of language and intellect, recognizing that true wisdom arises when one apprehends the interdependence and emptiness inherent in all phenomena.

Buddha Nature

Central to Mahayana philosophy is the concept of Buddha nature. This profound idea posits that all sentient beings possess an intrinsic connection to the awakened state. The understanding of Buddha nature reinforces the belief that enlightenment is not an external attainment but an inherent quality waiting to be realized.

Recognizing Buddha nature in oneself and others becomes a transformative practice, fostering a sense of interconnectedness and shared potential for spiritual awakening.

Six Paramitas

The Six Paramitas, or perfections, are fundamental virtues cultivated by Bodhisattvas to progress on the path towards enlightenment. These perfections encompass:

- Generosity (Dana)

- Ethical Conduct (Sila)

- Patience (Kshanti)

- Joyful Effort (Virya)

- Meditative Concentration (Dhyana)

- Wisdom (Prajna)

Each of these virtues represents a crucial aspect of the Bodhisattva’s journey, guiding them towards selflessness, compassion, and ultimately, the attainment of Buddhahood.

Key Sutras

Mahayana Buddhism boasts a vast collection of scriptures, each contributing to the richness of its teachings. Some of the key Sutras include the Lotus Sutra, the Heart Sutra, and the Diamond Sutra. These texts elucidate profound truths about the nature of reality, the Bodhisattva path, and the ultimate goal of enlightenment.

The Lotus Sutra, for instance, emphasizes the universality of Buddhahood and the skillful means employed by the Buddha to guide beings towards awakening. The Heart Sutra distills the essence of Prajnaparamita teachings, emphasizing the concept of emptiness.

Shunyata / Emptiness

The concept of shunyata, or emptiness, lies at the core of Mahayana philosophy. It challenges conventional notions of inherent existence and encourages practitioners to deconstruct their conceptual frameworks. Embracing emptiness leads to a profound understanding of interdependence and the dissolution of dualistic thinking.

Emptiness does not imply nothingness but rather the absence of intrinsic, independent existence. This realization is a crucial step towards breaking free from the illusions that bind individuals to suffering and ignorance.

May all beings be happy

May all beings be peaceful

May all beings be safe

May all beings awaken to the light of their true nature

May all beings be free