with 4 core logics of madhyamaka Thought

Uma or Madhyamaka means the Middle Way. Broadly, it refers to the overall path of the Buddha, free from extremes. But interestingly, it means the logics used to overcome all concepts of existence, non-existence, both and neither down to the most subtle level. Such concepts interfere with direct perception of jnana, wisdom.

Personally, I like Madhyamaka. I heard a very senior teacher criticize it as being not really good Buddhism, or something like that. I thought it arrogant to dismiss Nagarjuna’s most important contribution to Buddhism, but hey!

I find it helpful especially to contemplate the One and the Many and the Tiny Vajra. The key to figuring these out is the idea of the Middle Way. “Things do not exist” is not synonymous with “Things are non-existent.” This is tough to grok, but when we finally land there, the aha is very helpful.

Table of Contents

Definitions

- Madhyamaka: Madhyamaka is a school of Buddhist philosophy, founded by Nagarjuna and elaborated by Chandrakirti, that emphasizes the Middle Way. It overcomes extreme views and concepts about absolute reality.

- Middle Way: The Middle Way, in the context of Madhyamaka philosophy, overcomes the extremes of eternalism and nihilism. Practitioners overcome all concepts in the search for reality.

- Jnana: Wisdom or knowledge. Profound insight into the nature of reality.

- Emptiness: All phenomena lack inherent, independent existence. Instead, they are dependent and interconnected, devoid of self-identity.

Flow, the profound mental state, also called Peak Performance, can be attained with meditation and can be ‘triggered’ at will, with enough discipline. Guide to Flow Mastery will teach you how.

Schools of Madhyamaka

- Yogacharya: Promotes the view of Shentong, or empty of other view. Empty of other means the absolute is not empty of its own essence of being the ultimate. It is empty of the relative and all conceptual elaboration. The source of strong debates with Prasangika.

- Prasangika: Promotes Rangtong, or empty of self. Rangtong suggests that the ultimate is empty in and of itself.

- Svatantrika: The Autonomous school uses similar logics to Prasangika, but makes a sort of positive negation It states that reality is definitively empty, whereas Prasangika makes no claims whatsoever.

Explanation of Madhyamaka

Things are not as they seem

The Buddha

Nor are they otherwise

Four Extremes and the Middle Way

In the Middle Way, the understanding is often called the Freedom from the Four Extremes: Existence, non-existence, both and neither. This is a vast field of study. However, the basic premise is to undermine all mental constructs, however subtle, that define reality. It is meant to undermine concepts altogether, so that the mind can attain direct perception. Core analyses such as the One and the Many or the Tiny Vajra overcome normative notions of physicality and causality respectively.

The first level is true existence. The easiest entry into this is the notion of true existence. True existence is defined as physical permanence. In other words, if something truly exist, it must have existed in the past and must continue into the future. There can be no time at which it does not exist, ever, or its existence would be provisional. It would be a mere appearance. A truly existent object cannot be destroyed, but all physical objects can and will be destroyed by the ravages of time.

The second extreme is non-existence: the idea that phenomena are completely imaginary. This cannot sustain itself because objects do in fact. They can be utilized by beings for various purposes and fulfill functions. They have a relative, temporary manifestation, so utter non-existence does not correlate with our experience properly.

The third extreme is: an object is both existent and non-existent simultaneously. This is disputed because the flaws of both existence and non-existence accrue to the position.

The fourth extreme is that an object neither exists or does not exist. This position was argued as a non-Buddhist, and early Buddhist, school of thought. The position has no inherent meaning, hence it should be refuted on that basis alone. If things neither exist nor do not exist, in what possible way could they be thought of?

The problem with the four extremes is that phenomena are explained. They are conceptualized in each of these four approaches. In the Middle Way, phenomena are completely beyond all concept. They cannot be conceptualized or ‘understood’ in any way whatsoever in reality. Obviously, everyone, even animals, has some concept about phenomena.

The point is that these concepts are not the reality of phenomena in themselves. They are only discussions of them. It is critical to remember that Madhyamaka is essentially about overcoming conceptual fixations and ideas about reality. These concepts can be incredibly subtle and unseen.

The point of Madhyamaka is to understand emptiness. The aspects of it from the logic perspective help the mind to overcome conceptual fixation. It is a contemplative emptiness. The logics do not particularly reveal emptiness directly, but allow the student to overcome conceptual obstacles so that emptiness can reveal itself in meditation. Importantly, emptiness is a concept itself, so part of these logics are to undercut any fixation on emptiness as a thing.

How to meditate like a yogi

and enter profound samadhi

Prasangika Madhyamaka Logic

One and the Many – Refuting Physical Reality

The logic of the one and the many is a disproof of substantive existence of physical phenomena as such. It is a principle of logic that no thing can be both singular and plural. That would give it two conflicting identities or states of being. Nothing can simultaneously be one thing and two or more things. It makes no sense. The proposition is a direct contradiction. Also, if a phenomena is two things, then each of those is one thing by being divided.

Applying this to physical objects, let’s take the example of a car. It seems like a single thing, but it is composed of many things: wheels, engine, hood, seats, drive train, etc. This can be worked with in two ways. Firstly, do all these things exist separately from the car. Obviously, it is difficult to argue otherwise. Therefore, a car is both one thing – a car – and many things – all the components creating the car.

The second way to see it is to mentally dismantle the car. Remove the shell – doors, top, trunk, hood, etc. Is it still a car? Remove the engine, drive train, seats, wheels and so forth one at a time. Following each removal ask: Is it still a car? Eventually, it is definitely not a car, but it was when we began. At what precise point did it change from being a car to not being a car? Does that mean the piece removed at that point is the actual car?

Obviously, the answers to those questions are: No, the individual piece is not the car and There is no precise point at which it changes from being a car to not being a car? People would disagree on when it happened and most would be unable to point to a precise instant of change. If you remove the motor and drive train, some people would say that’s not a car anymore, you can’t drive it, but no one would say the motor and drive train are a car in themselves.

By taking out the individual pieces, you can never find the car. Yet the car appears when all the pieces are assembled. Therefore, a car is nothing more than the sum of its pieces. The lesson is counter-intuitive: there is no actual, truly existent car. It does not exist from its own side, but only as the sum of its parts. This logic can be applied to anything. Take a wheel on the car – is it the rim or the rubber ring? It takes both to make a wheel. Which is the tire – the side walls or the tread? Is a motor the pistons, the rings, the cylinders, the manifold, or the injectors?

Any example can be further broken down. Is a drop of water a singular thing? Well, it’s made of millions of molecules. Is a molecule a single thing? It can be broken down into Hydrogen and oxygen atoms. Moreover, a single molecule of water (or anything) does not have the properties of a collection of molecules. One molecule of water, for example, is not ‘wet.’

Taking a drop of water, remove molecules. At what point is there no drop of water? At that point, can you say the one molecule taken away was the drop of water? Obviously, that is absurd. The notion here: there never was a drop of water in reality. Only in appearance. Only in concept. There is the appearance and function of a car in relative reality, but the car per se as an singular, self-existent thing only exists in the mind. We apply extra layers of reality onto phenomena. Why? Because it’s useful, but we take that utility as reality.

Logically, we know the car is impermanent, but as soon as it gets a ding or scratch we become upset as if that was not supposed to happen. There’s a subtle idea of permanence that is subconsciously baked into the thing. If a part breaks, well, it’s made of parts, so they are going to break from time to time.

The place to land on this is as in the 4 extremes: the car does not substantively exist as a singular thing. We can disprove that. The car is not Non-existent because we see it. We use it for its function. It appears conceptually and we can drive it around. In a relative sense, the car has a significant reality. Therefore it is not non-existent.

Is it somehow both? Each of the problems apply to this idea.

Then is it neither existent nor non-existent?

These approaches are dealt with because specific traditions of philosophy advocated for them as the basis of reality. Therefore, Nagarjuna, Chandrakirti and others showed these traditions to be flawed in their ground of logic. This fourth logic – neither existence nor non-existence – is said to be the Peak of Existence. It is the highest realm possible in Samsara.

This is why it is refuted in the Madhyamaka – to help the philosopher meditators overcome the most profound hurdle there minds have created against enlightenment. The ability to focus on this concept – neither existence nor non-existence – creates a mind so subtle that this most intangible, abstract, aconceptual approach to reality becomes its reality.

The problem? This is still a conceptual overlay. Neither existence nor non-existence is a conceptual idea. That conceptual idea will get you closer to emptiness, but so long as you fixate on the idea as “Yes, that is the nature,’ that very subtle concept will block that actual direct apprehension of reality itself.

Many meditators who take this general approach seriously wind up at this fourth concept without realizing it. It IS very subtle. It IS very profound. It is powerful. The meditation is incredibly stable, potentially lasting for billions of years as a formless, non-physical entity. It has great vividness, bliss and clarity. In fact, it represents the perfection of shamatha.

In the end, however, it is a mental identity. It is a means of reifying the self against a conceptually constructed reality. It is an explained reality and reality itself cannot be explained or expressed as a concept. While concepts can be used to guide beings to reality, it is absolutely essential to realize the distinction between the concepts and the direct experience. It is also essential to realize that meditation on subtle concepts will generate profound states of mind that are still in error if they are taken as reality. This is among the most common errors when meditation takes hold.

It is important even to not reify the idea that reality cannot be conceptually expressed because that becomes its own concept. The whole thing becomes almost maddeningly difficult to establish. Why? Because establishing something, reality for example, is a conceptual exercise.

The Mahayana explanation is interesting. You cannot say anything is essentially true, so how does it come about? How does it arise? What is the cause? The next section answers that question.

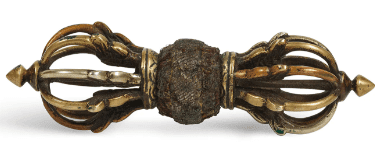

The Tiny Vajra – Madhyamaka Cause and Effect

Where the One and the Many refutes substantive physical objects as a conceptual reality, the Tiny Vajra refutes definitive ideas of causality. The vajra is an indestructible weapon that destroys all notions of causality, including acausality. Acausality is simply a notion of causality. Again, we are dealing with conceptual formulation of reality here, and showing how they do not hold up to close scrutiny.

From the four extremes, there is either causality, acausality (randomness), both, or neither.

The first is actually among the most difficult to dispense with. When studying this, it’s so counterintuitive, so seemingly illogical, that the mind immediately rejects it. How could someone make the case that causality doesn’t exist? But the rejection is misunderstanding the core argument. The core argument is not that causality does not occur. It is much more accurate to say that causality cannot be conceptually described. All concepts are flawed.

In that spirit, I urge you to keep with it. I’m trying to make the explanation as clear and simple as possible. The logics are somewhat abstract. It can be very helpful to study then contemplate the logics, then return to reread them. There are some books that exist on them. It is helpful to read it from differing perspectives. Because they are epistemological in nature, rather than empirical, the untrained person will misinterpret. It takes a few iterations to fully understand.

The problem with the Tiny Vajra is not that the logics are so difficult or subtle. It is that they are so contradictory to our baseline interpretation of the world. Therefore, for explanation, it’s better to begin with the second extreme – acausality. Acausality means that causality is simply absent. Events happen at random. If you plant a seed, it may sprout and it may not. It may grow up, and it may not.

Actual spiritual traditions exist that espouse genuine acausality. But it’s very easy to disprove this with the wheat seed. If the seed sprouts, it will always grow wheat, never an oak tree. You cannot specifically say there is Acausality as a thing. If you release a rock from your hand, it always falls down, never up. In this sense, causality is so intuitively obvious that it is almost insane to say things are acausal. Thus Madhyamaka refutes Acausality.

However, it also refutes causality. This is where it gets challenging, because we are trained implicitly in the Law of the Excluded Middle. If you refute causality, you must have acausality. If you refute acausality, you must have causality. But if we drop the Excluded Middle we can refute them both. We simply do not state anything as a definitive case.

The key point of Madhyamaka Logic is refutation of all positions without establishing any alternate position.

This is a leap for most people. If you say X is not True, then most people take that to mean, therefore Not X is true. This is NOT the system in consideration in Madhyamaka. Madhyamaka simply refutes any conceptually stated position about the ultimate reality of any phenomena.

How is causality refuted? In the details. The most intricate details of explanation do not hold up to close scrutiny. They self-contradict. Certainly, the appearance of causality arises as explained above. However, the definition of Cause and Effect cannot sustain itself.

A Cause is defined as ‘The producer of an effect, result, or consequence.’ Here we are specifically focused on the first – producer of an effect. An Effect is defined as ‘Something brought about by a cause or agent; a result.’ Therefore, a Cause depends on an Effect for its existence and vice versa. You cannot have an Effect without a Cause nor a Cause without an Effect by definition.

An inescapable implication is that the Cause must exist before the Effect. However, this creates a logical paradox. Since something cannot be called a Cause until an Effect exists to make it a Cause, it is not a Cause until after the Effect arises. However, the Cause must precede the Effect in time. But before the Effect arises, it is not yet a Cause. After all, the Effect may not arise – it cannot be guaranteed. Sometimes the wheat seed does not sprout.

If the Cause only exists after the effect arises, it has no need to exist. Why produce an Effect that already exists? How would that even work? Cause and Effect cannot be concurrent.

Another way to look at this: the Cause must cease before the Effect arises by definition, since Cause precedes Effect. Once the Effect arises, the Cause, by definition, can no longer exist. To clarify, this is not saying that the phenomena as such must cease to exist, only that its identity as a cause no longer exists. The Cause as such MUST precede the Effect for causality to have any meaning whatsoever.

Likewise with the Effect. Before the Effect arises it cannot exist, obviously. When the Cause gives rise to the Effect, if they do not exist at simultaneously, there is not temporal connection between them. If the Cause is gone before the Effect arises, then the Cause could not possibly give rise to the Effect. How can a non-existent thing give rise to an existent thing? Importantly, we are talking about very precise and small measures of time – an instant.

If the Cause exists at the same time as the Effect, it cannot give rise to the Effect because the Effect has already arisen. In other words, the logical approach to Cause and Effect cannot account for that fact: Cause cannot exist before Effect arises, but they must exist simultaneously in order to have a temporal connection allowing for the arising of Effect.

This is a problem with the conceptual understanding of Causality. When precisely analyzed the definition holds an inherent contradiction. This is not saying that Acausality is the nature of reality. It is saying that Causality cannot be conceptually established in a precise and meaningful manner. It is beyond concept and explanation. Any explanation can be defeated by precise analysis. The logic is very difficult.

This appears to be mere sophistry, but it’s not really. That’s because we aren’t trying to establish a truth. It is trying to reveal inconsistencies in a conventionally obvious, universally believed truths. It is saying the concept of Cause and Effect doesn’t quite work at the most subtle level.

Cause and Effect cannot explain reality in an accurate and precise manner because the definitions preclude a Cause and an Effect existing simultaneously, and the very idea of causality precludes a time-gap between a Cause and an Effect. In other words, the argument defeats itself.

All arguments have inherent self-defeating propositions. This is the pith of Madhyamaka logics.

Causality, in the way its defined, is impossible to definitively establish with great precision. Acausality likewise does not work because at coarser level, Cause leads to Effect in a predictable manner. Both Causality and Acausality combined is absurd because it clearly self-contradicts and further takes on the faults of both ideas at once.

If you take on the more subtle fourth extreme and say “Well, it’s neither Causality nor Acausality,” then you are left with no explanation for phenomena, while still attempting to establish this position. Though it does in fact seem awfully close to what we’re looking at, it fails by being conceptual. One of the reasons for it is that concurrent traditions actually espoused this around the time of the Buddha and later.

Three ways have been put forth to describe phenomenal reality. First, it is like a magical illusion. There is mere appearance but no logical, comprehensive explanation will suffice.

The second description is interdependent arising. All phenomena exist in relation to all other phenomena. When the causal and conditional factors, each existing in dependence on numerous other things, dissolve, then the phenomena they support will also dissolve. Everything arises from and gives rise to other things. In other words, the phenomena are less real than the interdependent ‘net’ of relative reality. This perspective removes the fixation on solid objects, replacing it with a more felt sense of connectedness between the ‘self’ and between all phenomena. It is an energetic approach to existence and when meditated upon skillfully, the experience is profound.

The third approach is separating concept from experience. The thing is not the idea about the thing, the word used to point it out. We often unconsciously think when we say the name of something, it is the thing. We know the word is not the thing, but we subtly make the mistake of not separating the two. We think ‘dryer’ is synonymous with the hunk of metal we use for laundry. But in reality, there is no connection.

Investigation of the Result: refutation of existent or non-existent production

The effect or the result in the cause and result can be analyzed as either existent or non-existent. Neither of the 2 situations holds up. Firstly, if the effect is existent before the cause creates it, then there would be no reason for a cause. The very concept of a cause is to bring about an effect, therefore the cause must precede the existence of the effect.

If the effect is not existent and the cause is said to bring about the effect, to bring it into existence, this is nonsensical. You must have a phenomena (the effect) which is non-existent before the cause produced it and existent after the cause came about. Why? Because then the phenomena is a single thing with two contradictory states: existent and non-existent. In other words, the effect before the cause occurs must be the same as the effect after the cause creates it in order to mean anything. However a non-existent phenomena is inherently different from an existent phenomena.

This is not meant to refute the conventional approach to cause and effect. If you plant an acorn, only an oak sprout can emerge. The point: it is impossible to truly capture the subtle intricacies of how things appear to arise.

In the system of the Buddha, this arising comes about via dependent origination. Rather than thinking of ‘existing’ or ‘not existing’ it is more correct to say they appear without possessing true existence, somewhat like a magic show. All of conventional reality is said to be like this.

Otherwise you would have non-existent phenomena transforming into existent phenomena and back into nonexistent phenomena. But a nonexistent phenomenon is distinctly different from an existent phenomenon.

They are all merely appearances on the conventional, relative level and ultimately they are empty of their own essential identity.’

Jamgon Mipham the Great

Within this system, the mind wants to land on the 4th extreme – things must be neither existent nor nonexistent, but somewhere in between. This would seem to be the logical conclusion. It is also a philosophical position of certain sophisticated spiritual traditions. These schools have a conceptual profundity to them, there is no doubt. The experience of neither existence nor nonexistence is in fact a highly profound way to experience relative reality. It is not ultimate reality. There is still a ‘basis for conceptual reference.’

Because of that conceptual basis, the 4 extremes cannot be discarded or surpassed by the mind. They form a conceptual barrier to direct apprehension of reality beyond any concept whatsoever. This state, once achieved, is the prasangika contemplations and meditations. Prasangika is better for contemplation, for cutting through illusion and concept.

However, it tends toward a subtle negation of even valid meditation experience. This creates an obstacle, because when reality emerges, the Prasangika training will subtly overcome the valid perception. The sharp clarity developed is distrustful of any experience, seeing it as a concept.

Once the these conceptual fabrications have been eliminated through contemplation, then the meditative state of primordial awareness beyond duality, infused with luminosity, can emerge and transform the ordinary person into reality itself, into Buddha.

Refutation of Time as truly exist

Time is one of the great and overarching phenomena in our life. It dictates all aspects of everything we do. It inescapable. But does it exist as a real thing?

In physics, the idea of time is movement of physical objects through space. If these movements reverse their movements exactly (all objects of course), then time reverses. There is also the countervailing and contradictory approach that entropy defines time by making phenomena more chaotic in the scientific sense, which is to say more uniform and homogeneous in structure. When absolute entropy is achieved, a sort of cosmic soup with unchanging temperature, time could theoretically cease.

In Madhyamaka, time can be analyzed be breaking it into smaller components. If Time is real, then each instant of time must also be real. Therefore every instant of time, past, present and future must be real. But are future instants real? They have not arisen yet and cannot be accurately predicted. If they are real, then all of the future is predetermined because a real instant must occur exactly in a single way. If it does not occur in that pre-specified way, then how could it be real? It became a different instant.

We also have several laws of physics, like Chaos Theory and Quantum Theory, which show that reality is impossible to predict. Therefore, the future is not pre-determined. (Whew! that was scary for a minute.)

Are past instants real? They seemingly happened, but they are no longer accessible. Once a moment happens, so far as we can know, it is gone forever. Something with this trait is hard to call ‘real’ in any meaningful sense of the word.

So we’re left with the present, which certainly appears to be ‘real.’ We can touch it, see it, hear it, and experience it. The present moment is incredibly obvious and in a sense, it’s all we really have. In that sense, we can say that only the present is real. But is it so?

Imagine an instant of time in the very near future – few seconds out. It’s not real because we haven’t experienced it and any idea about it could change. As it arrives and becomes a present instant, what happens? Does it become ‘real’ for a brief flash, then become unreal again as it recedes into the past? This is almost a silly concept. Reality having so little substance is nonsensical.

By this method, we can see that Time is not real per se, despite it’s overwhelmingly powerful effect on us. Well, we aren’t real either.

When we say something Truly Exists or is Real in this system of logic, we mean it exists independently of time. It has always existed, exists now, and always will exist. Otherwise, when it dissolves, it goes from being Real to Not Real. But how can something Real become Not Real. It makes no sense. We’re talking about two different things.

This is somewhat the inverse of the One and the Many. It’s somewhat absurd to say that a Real thing (time) is composed of a series or collection of Unreal pieces (instants of time). Therefore time cannot be said to truly exist.

Of course the same logics apply: is Time definitively non-existent? Obviously, that would cause everything to freeze without ever moving. So it’s not definitely non-existent. Is it both? Then, as in the earlier examples, it would accumulate the flaws of both logics.

Is it then, neither Real nor Not Real? If that were the case, we could not conceive nor explain it at all. It leaves us with no idea to relate to. People have used this approach in the past. However, it is simply a non-explanation posing as an explanation.

Therefore we’re left at a similar place as the Tiny Vajra. Time is a magical illusion. Time cannot be adequately explained. It vividly and powerfully appears, controlling all aspects of our experience, but cannot be definitively established.

Criticism

Silence

C

If reality is beyond description, then that leaves the realized person with nothing to say because it is beyond description. Discussion becomes meaningless.

Reply: While reality is beyond direct statements about it, it is NOT beyond negate false concepts about it. Therefore the discussion is meaningful, because it helps meditators cut away error, revealing the actual nature.

Nihilism

Critics claim that the concept of emptiness leads to nihilism.

Reply: Untrue. This is a mistaken apprehension of emptiness, though understandable. Emptiness does not dispute the arising of appearances in relative reality. It disputes their true existence, but allows for provisional existence of various types.

Infinite Regress

Prasanga / negation of all positive assertions, leads to an infinite regress of negations, wherein nothing can be asserted.

Reply: True, in that nothing positive can be asserted. However, positive assertions are not the goal of the system. The goal is to undermine all positively asserted concepts about reality. Undermining the interfering concepts allows wisdom to manifest directly.

Self-contradictory

Criticism: Madhyamaka uses language and concept, but claims that language and concept are inherently flawed. How then can the system provide any accurate understanding?

Reply: It can’t provide that, because there is no such thing. Instead, it uses the unfortunately flawed tools to cut through conceptual fabrications.

No positive ontology

Criticism: Madhyamaka has no positive ontology, insisting solely on a negating outlook. This leaves a philosophical void.

Reply: Any positive ontology would merely construct a set of concepts about what is ultimately beyond all concept. As such, it would interfere with direct experience of the ultimate.

FAQS

What is the Madhyamaka in Buddhism?

The Middle way Philosophy, founded by Nagarjuna in 153CE, 650 years after the Buddha taught. It disputes all conceptual approaches and emphasizes the ineffable nature of reality.

What is Madhyamaka philosophy?

The middle way philosophy is to not engage in beliefs about true existence, non-existence, both and neither.

Is Madhyamaka the same as Mahāyāna?

No, Mahayana means Great Vehicle and includes all bodhisattva modes of view and practice. Madhyamaka is the philosophical and reason based method of ascertaining emptiness and is a core method of Mahayana understanding and practice.

Summary

Many more Madhyamaka logics exist to explain overriding phenomena: motion, thoughts, sensory experiences, solidity and so forth. But in the end, they all come down to similar ideas as these. The idea is to make no attempt, however subtle, to explain things. These logics help to unearth subtle, unseen concepts we hold about reality. We can use the logics to overcome those subtle concepts and ideas by showing how they cannot actually match up to what is actually happening.

May all beings be happy

May all beings be peaceful

May all beings be safe

May all beings awaken to the light of their true nature

May all beings be free