Ultimate Guide for beginners

Part I

Tibetan Meditation in Brief

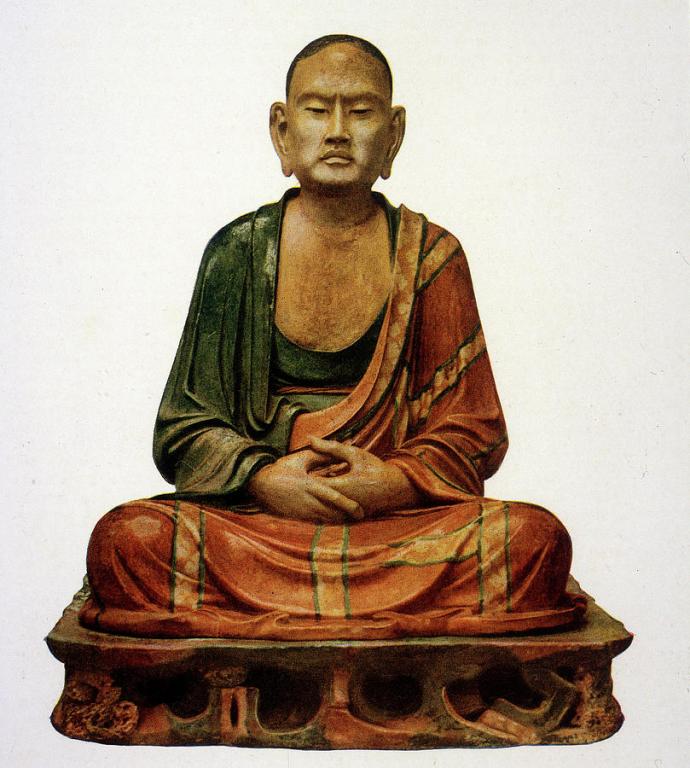

Meditation in Tibetan Buddhism is a broad-ranging system based on the 9 yana journey, distinguished by a strong focus on the Tantric yanas (vehicles).

The core of these is increasingly direct meditation on the nature of mind, characterized as luminous empty awareness, often visualized in deity form. This is the most rapid path to enlightenment. .

Ultimate guide to Tibetan Buddhist Meditation, part II: Vajrayana

Ultimate Guide to Tibetan Buddhist Meditation Part III

Table of Contents

Detailed Explanation of Meditation System

Introduction to the meditation

This system of Tibetan Buddhist meditation techniques is not solely meditation. It is incomplete without the view – the understanding of reality. This view is extensive, highly detailed, and has been explicated over many centuries. Especially beginning with Padmasambhava, Guru Rinpoche. However, the origins date back to Buddha Shakyamuni. When King Indrabhuti asked for a path that allowed him to remain as king so that he could wisely rule, the Buddha sent his monks from the chamber and taught the Kalachakra tantra to Indrabhuti, who attained full realization and ruled wisely thereafter.

We have three types of tibetan buddhist meditation: Hinayana, Mahayana, and Vajrayana. Within that, however, there are essentially 9 major progressive categories and thousands of varieties. So, what is Tibetan meditation?

How to meditate like a yogi

and enter profound samadhi

Hinayana Meditation

The stages of meditation begin with Shravaka / Pratyakabuddha yanas – Hinayana – or the Narrow Way, also called the Vehicle of discipline. This foundational vehicle explores the selflessness of the individual.

Hinayana includes detailed explanations of the nidanas (karmic chain), skandhas (heaps of the self), the four noble truths, vinaya (monastic codes), and so forth. Meditations (explained below) are the four reminders, shamatha, and not-self.

The Four Reminders

- Precious human birth. This is being born as a human with sufficient food, shelter, safety, and the opportunity to practice the dharma.

- Impermanence and death. Life is temporary, death comes inevitably without warning.

- Karma is inescapable. All actions entangle one in karma, so you must act to create positive tendencies.

- Shortcomings of samsara. Samsara is in essence suffering – birth, aging sickness and death, wantingness, hunger, deprivation, physical pain, loss, etc are part of every life.

The point of meditating on these four reminders is to create a sense of meaning and urgency. Samsara can be escaped. Karma can be stopped in meditation. But you must act now while you have a life that can be used to establish the dharma because when death comes it is too late.

Shamatha

Shamatha is meditation per se. It means dwelling in peace. The method is profound focus on an object. The object can be anything – a statue, a rock, the breath, or emptiness. The idea here is to develop the muscle of meditation so that when you apply it to any object, you can actually meditate more and more deeply on that object. Choosing certain objects creates insight. That is vipashyana meditation.

Hinayana Vipashyana meditation

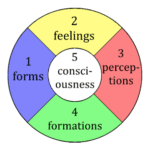

Hinayana explores one-and-a-half-fold egolessness, primarily egolessness of the self in order to attain liberation. This style of meditation focuses on breaking the seemingly solid, independent singular self down into its component pieces – 5 skandhas, 12 nidanas, and so forth. This extends to focus on the lack of any fixed elements in the self. All these components are constantly changing. Experience of the self is moment to moment, unstable, and without true identity. This seems counter-intuitive to our experience but is understood in study and revealed in meditation. Sosa Tharpa – Individual liberation from samsara – is the goal of this vehicle.

Mahayana Meditation

The next vehicle is Mahayana – the Great Vehicle. Great refers to the vastness of the view. The Mahayana practitioner commits to the liberation of all beings in samsara. The focus here is on compassion. This is the bodhisattva path which includes the well-known eight-fold path, the ten bhumis, and the five paths. Key meditations (explained later) here are bodhicitta, tonglen, resting in the alaya, vipashyana, seeing the illusory nature of reality, and the four immeasurables.

Flow, the profound mental state, also called Peak Performance, can be attained with meditation and can be ‘triggered’ at will, with enough discipline. Guide to Flow Mastery will teach you how.

Bodhicitta meditation

Bodhicitta means awakened heart / awakened mind. It unites the two fundamental Buddhist components – wisdom and compassion – considered to be ultimate and relative bodhicitta. Bodhicitta is considered to be the heart and soul of all Buddhist practices. With it, everything is possible, without it, nothing on the path can be truly accomplished. The essence is the heartfelt longing to experience reality and to alleviate the suffering of all that lives.

The meditation comprises a certain amount of study and contemplation. The practitioner must have a strong understanding of what is meant by compassion and by wisdom. You can meditate on both directly, alternating between study, contemplation and meditation. It is very helpful, if not essential, to increase the longing for ever greater compassion and wisdom. See here for a detailed explanation of bodhicitta.

Note: most of the slogans herein are taken from the Seven Points of Mind Training attributed to Atisha. The translation used is Chogyam Trungpa’s Training the Mind and Cultivating Loving-Kindness, a highly recommended, fundamental text on all aspects of bodhicitta.

Tonglen – Relative Bodhicitta

Sending and taking should be practiced alternately. These two should ride the breath

Atisha

Tonglen means sending and taking. First, establish a base of shamatha. Then briefly open to shunyata, emptiness, the non-solidity of reality. This is wisdom. It is essential to establish a basis of shunyata in order to purify the negative karma taken in during the main part.

The second piece is to think of someone who is suffering. Maybe a memory of a situation that made your heart ache to relieve the person’s pain. Then draw out that pain on your in-breath, bringing it into yourself so they no longer experience it. Don’t worry about it working or not, just do it faithfully. Experience the pain, and give out relief, joy, the opposite of what they’re experiencing.

Negativity is visualized in the form of thick black darkness, painful, claustrophobic, and heavy. This is drawn out of all beings as you breathe in. Extend the breath some to draw in as much of this as possible. Literally meditate that you are taking away actual pain and negative karma from beings in this form. It goes into the heart, where it is purified in emptiness. This is key, as then it can cause you no real harm.

Following that, send out goodness in the form of light. There is no need to overly strategize this. Keep it simple. Anything good goes to others, anything bad comes in. This counters the ingrained tendency to always think of oneself. Reversing this tendency is the key to genuine happiness. True joy cannot come from self-centeredness, but only from caring for others.

Doing so reveals deep, endless, infinite treasures of goodness that exist within oneself. The more you are willing to take in pain and give goodness, the more goodness you find to give. Goodness is your nature, therefore it cannot be exhausted. It is not a physical thing, so you can never give it all away. It is tapped into the entire universe and is beyond your small self so that vast ocean can never be drained. Give it away and you will access more and more and more without limit. That’s how it works.

The sequence of sending and taking begins with yourself

People are in a lot of pain. Everyone has some pain somewhere. The idea of tonglen is realizing that no one is coming to help them. Not really in a way that counts. It’s up to you. Take in the pain to begin with, as soon as you see it. This applies in real, immediate meditation. In situ, as they say. When you see someone suffering, instinctively feel that you are relieving that pain by breathing it in. That becomes the first instinct if you do enough tonglen.

Then breathe out goodness. They could use some relief, some light, some feeling of goodness. This is not martyrdom – you wouldn’t ever let anyone know you’re doing this amazing thing. You are overcoming small-mindedness and territory. You are reversing the self-centered habits of the world. The world needs it so badly. If everyone did Tonglen daily, it would be a much better world.

Tonglen is the heart of the Buddha’s compassion. It is difficult to do, but gets much easier. Then it becomes joyful, profound, and natural. Try it.

Resting in the Alaya – the essence

In Buddhism, the mind is composed of eight consciousnesses – the six sense consciousnesses: sight, smell, taste, touch, hearing, and the consciousness of mental events – the seventh – defiled consciousness which creates the separation and the sense of self – and the eighth consciousness, the alaya. The alaya has two aspects – one is a sort of consciousness, a vijnana, which means divided mind. Awareness is separated into subject and object. It’s analogous to an intent to relate to the world.

The alaya principle is deeper than that. It’s the stuff all that we are as individuals. It’s a storehouse of karma, but also a connector to the deeper basic awareness composing reality at the core. This principle is analogous to light. It is not consciousness, but its essence. The alaya is the creator of our world. Resting in it means going beyond the ordinary preoccupations of ourselves and resting in the basic, essential quality of mind at its deepest level. This mind is not caught in the petty concerns of our lives but is simply experiencing or even simply the ability to experience.

This is the practice of ultimate bodhicitta. Developing this skill in meditation allows for deeper and more profound meditations. The alaya is not the end goal of Buddhist meditations, but a very significant step on the journey. It allows you to expand on and penetrate genuine vipashyana.

Examine the Nature of Unborn Awareness

In the space of resting in alaya, vipashyana is deepened by this examination. Unborn awareness means the native stuff of mind itself. It is unborn because it never came into being in any particular way. The mind has always been able to perceive, that’s what it does. That defines mind. So examine that. This is how to ‘know thyself.’

In postmeditation, be a child of illusion

Take the insight revealed in the examination of awareness and apply it to daily life. This is a fascinating practice. Simply engage in activity with the thought, “this is an illusion. I am a child of this illusion.” The illusion, of course, is the solidity and permanence of life. Everything we have, know or see, all our friends and possessions, none of it will last. All of it will be gone in a hundred, a thousand or a million years. This feeling of permanence and fixedness is an illusion.

Regard all dharmas as dreams

Dharmas here means phenomena. Viewing all that you see, experience and especially think as dreamlike creates a powerful means of dealing with the seeming thickness, fear, heaviness and intractability of your life. It’s a dream, in a very meaningful sense. Once a dream is over, it’s over. This life will come to end and it will be over forever. It’s quite possible to meditate on life as simply a long dream.

Insight Meditation – Vipassana / Vipashyana

Vipashana meditation is characterized by insight into emptiness as the nature of phenomena. The seed teaching of this is the Heart Sutra – officially titled the Sutra of the Heart of Transcendent Knowledge. It’s a relatively blunt statement of emptiness. Key teachings are Nagarjuna’s Mūlamadhyamakakārikā (Fundamental Verses of the Middle Way), Chandrakirti’s commentary Prasannapadā (Clear Words), and his Madhyamakāvatāra (Introduction to Madhyamaka). Thousands of other commentaries exist.

Meditations include focusing on the Cittamatra (mind-only) school of meditation, Svatantrika, the lack of inherent reality in phenomena, and the Middle Way school of teachings. The central idea is the Buddha’s second turning of the Dharmachakra – the wheel of teaching.

Taking the Heart Sutra as the reference, the Buddha is in a state called Profound Illumination. Shariputra asks Avalokiteśvara, the Great Bodhisattva, how to meditate on prajna-paramita – transcendent insight. Avalokiteśvara replies

Form is emptiness, emptiness also is form

Heart Sutra, Buddha Shakyamuni

Emptiness is no other than form

Form is no other than emptiness

He then continues to list all other components of internal and external reality as emptiness. There is no Four Noble Truths. Even the great attainments of the Buddha are empty. “There are no characteristics.” The Buddhas therefore attained enlightenment by means of the prajnaparamita, the insight into emptiness. There is a mantra

Om gate gate paragate parasamgate bodhi svaha

The letter is e is pronounced as a long a, like in say. The a’s are short, like in Sara. The i sounds like a long e, like in be. The method afterwards was to recite the Heart Sutra, then do one or more malas (108 beads) of the mantra, then contemplate emptiness silently.

The Four Immeasurables

The four immeasurables are Loving Kindness, Compassion, and Sympathetic Joy. The textual recitation is something usually like

May all beings enjoy happiness and the root of happiness

Four Immeasurables Virtues of Buddha

May they be free from suffering and the root of suffering

May they not be separated from the great happiness devoid of suffering

May the dwell in the great equanimity free from passion, aggression and delusion

Each line corresponds to one of the immeasurables listed above. Recite the text, typically after refuge and Heart Sutra, then contemplate one or more of the immeasurables and consider how to apply it in your life that day.

May all beings be happy

May all beings be peaceful

May all beings be safe

May all beings awaken to the light of their true nature

May all beings be free