5 schools of Buddhism

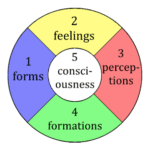

Buddhism approaches emptiness or shunyata in 5 levels – Not-self / Shravaka, Mind-Only / Chittamatra, Space-like / Svatantrika, Empty of Self / Prasangika, Empty of Other – Shentong. Each builds on the previous as follows.

Secrets of Meditation for Anxiety

Like millions of people, you may have suffered from anxiety for years. Meditation, yoga, peaceful music – it never works. It takes too long, and it’s not stable. Why? Because peace is treated as a cause for freedom, but it’s not – it’s the result. The cause to free yourself from anxiety is completely different.

Click now to Overcome Anxiety for good.

Table of Contents

Shravaka Doctrine: emptiness of self

The first level of voidness in Buddhism is non-self. Atman in Buddhism is the self. Anatman negates this.

The Shravaka school of emptiness focuses on Not-Self, or the emptiness of a singular, independent, truly existent self. The goal is soso tharpa, individual liberation from suffering, release from rebirth, and Nirvana after the death of the body.

Shravaka means hearer, or one who listens to the teachings of Buddha. This is in contrast to the Pratyekabuddhas who practice solitary realization. Shravaka doctrine teaches the emptiness of the solidly existent self. The self is assumed to have 3 characteristics: singularity, permanence, and independence.

These assumptions are unexamined and cannot withstand examination. Thus the Shravaka process it to hear the doctrine, contemplate it to create a strong understanding and clarify concerns, then meditate until realization. Realization means that the student now sees the world in that way, i.e., the self has no true existence.

Realization is stablilized experience of insight.

This is not to say that the self is non-existent altogether. There is a personality, but it is made of parts that constantly change and shift. But this differs from the innate assumption of a singular, self-existing, and permanent ‘self’. Such a self would exist in some sort of unchanging isolation.

Let’s examine these 3 traits

Singular Self does not exist

if a singular self exists, it must be findable as one thing. But what would that one thing be? The body? The body is made of many parts, so it could not be the body in total as it is logically impossible to be both one thing and multiple things. Is it the thoughts or feelings? The same logic applies as there are many thoughts and feelings. These constructs are referred to as the Skandhas or heaps, the constituents of a sentient being’s existence. This only leaves one with consciousness itself or some other, hidden factor.

Technically, consciousness can be ruled out because it is defined as consciousness of something. Therefore to be conscious, there must exist in the consciousness both a subject and an object. Hence it cannot be singular. Moreover, the contents of consciousness constantly change based on real-world occurrences, therefore consciousness is both impermanent and dependent on external factors.

Shravakas also contemplate and meditate on the 12 nidanas or the links of dependent origination. This is a means of explaining karma.

No permanent self exists

A key method to look into not-self in consciousness: consciousness is, in essence, a string of moments of awareness. If these moments are differentiable, one from another, by various factors, then consciousness is not unaltering (independent of external circumstances like time) and is not permanent. This means: each instant can be seen as a separately arising consciousness. To make this more clear: is the consciousness of an infant the same consciousness in that person as an adult? Most people would not agree. These momentary divisions of consciousness into both instants and dual objects are called vijnana – divided knowing.

Western science has the same conclusion: the ‘self’ is in fact a composite of many factors. But why do we act as if we have One, Durable, Unaltering self? Why do we protect this imaginary thing? Clearly, we are subject to an hallucination, one that affects virtually everyone and everything alive.

No independent self exists

An independent self would exist from its own side. However, the self as such exists only insomuch as it is defined by numerous factors. It must be labeled in language. It must be experienced by a watcher. It must be witnessed from outside to verify such an existence. It cannot be altered by external circumstances or it would not be independent.

Shravaka Meditation

Taking Refuge

Begin with taking refuge in the 3 jewels of Buddha, dharma, and sangha. Practice shamatha (Calm-abiding) Meditation: cultivate single-pointed concentration and tranquility by focusing the mind on a chosen object of meditation, such as the breath, a visual image, or a mantra. The goal is to develop stability of mind. Calmness and clarity typically emerge from stable focus. More on that here.

Proceed with vipassana (insight). Look into the existence of the supposed self. Where is it? What does it look like? Is it immaterial? If so, in what manner does it exist? Hold a question in mind and seek the actual existence of a singular, independent, and permanent self.

This analysis and meditation yield an interesting insight. The self is merely a name for a chimera. The Buddha didn’t exactly say there is No Self. He said, Can you find it? I cannot. Knowledge of emptiness consists of studying and contemplating this counterintuitive explanation. Realization follows from thorough meditative searching for the self within one’s mindstream.

This realization, combined with meditative stability, allows the meditator to enter Nirvana, the state beyond suffering, or Peace, extinction of the self, at the time of death. By seeing Not-Self, the mind is not compelled by Karma to take rebirth. This is not the full enlightenment of the Buddha, however.

Vipassana (Insight) Meditation

Vipassana meditation involves the direct investigation and observation of the nature of experience and phenomena. Practitioners develop mindfulness and awareness to discern the impermanent, unsatisfactory, and selfless nature of all phenomena. This practice cultivates insight into the Three Marks of Existence (impermanence, suffering, and non-self) and supports the development of wisdom and liberation.

Anapanasati (Mindfulness of Breathing)

This meditation practice involves focusing one’s attention on the breath as it naturally flows in and out. By observing the breath with mindfulness, practitioners develop concentration, stability, and awareness of the present moment. This practice helps cultivate a calm and focused mind, leading to deeper insight and understanding.

Contemplation on the Four Noble Truths: Shravakas often contemplate the Four Noble Truths during meditation. This involves reflecting on the truth of suffering, the origin of suffering, the cessation of suffering, and the path leading to the cessation of suffering. By investigating these truths with mindfulness and wisdom, practitioners deepen their understanding of suffering and its causes, ultimately leading to liberation.

How to meditate like a yogi

and enter profound samadhi

Yogacharya / Chittamatra / Mind-Only

The Chittamatra school of emptiness, also known as Yogacharya (also spelled yogachara) or Mind-Only school, claims that all phenomena are mind essence. The duality of matter and mind, perceived and perceiver, is an illusion conquered through correct view and rigorous meditation.

With our thoughts we make the world

Shakyamuni Buddha

The previous stage of Shravaka Not-Self meditation leaves a fundamental ignorance of reality behind in the mind. While it is very good at dealing with emotional obscurations, especially in formal practice, it does not extend off the cushion as well and does not address the cognitive obscurations. These are the fundamental errors in view concerning the nature of reality.

According to the Buddha, ‘The realms of existence are only mind.’ A more down-to-earth manner of understanding this: without a mind, there can be no perceptions or ideas about reality. The mind creates any understanding of the perceptions as brought in through the sense organs. Those understandings or concepts give us a structure to the world. We focus on aspects that matter to us and ignore all else. To a fly or a plant, excrement appears as food. To us it is filth. This logic of differing aspects applies to all objects the mind can conceive of.

Chittamatra philosophy asserts that the ultimate nature of reality is mind or consciousness. It emphasizes the subjective aspect of experience and argues that all phenomena are ultimately mind-dependent and arise as appearances within the mind. According to Chittamatra, external objects and events are projections of consciousness and do not have an inherent existence separate from the mind.

Mind is the final reality of Cittamatra philosophy.

A core example is the idea of ‘solid’. The mind cannot encounter a solid object. The mind can only experience sensory details transmitted to it. The mind itself cannot extend anything into the world, nor can physical objects exist in the mind. Hence the mind cannot experience solidity directly, only the concept that it has of solidity. This concept is an interpretation based on input from the 5 senses.

Chittamatra also puts forth the idea of “eight consciousnesses.” These include the five sense consciousnesses (related to sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch), the mental consciousness (which processes thoughts and emotions), the 7th consciousness (which looks at the perception/perceiver and conceives them to be separate), and the alaya-vijnana (the foundational consciousness that serves as the basis for all other consciousnesses and holds all karmic imprints). Analyzing and exploring these consciousnesses in meditation allows the meditator to dissolve the illusion of a singular self and the illusion of a solid reality.

3 natures of Chittamatra

Finally, Chittamatra posits the 3 natures: imaginary, dependent, and truly existent.

- The imaginary nature is the subject/object split. Separate independent entities have no existence whatsoever. They are imaginary.

- The dependent nature is the experience or appearance – the display itself, the luminous mind, but not the individual entities appearing within.

- The truly existent nature is emptiness, without physical form or duality of any kind.

The dependent nature is said to have true existence. This became the point of contention, in terms of explanation, for the later Madhyamaka schools.

Chittamatra emptiness Meditation Methods

Meditation practices in Chittamatra, or Yogacharya, cultivate insight into the nature of mind. Cittamatrans seek to understand the deepest qualities of mind itself. Key techniques of the meditation:

Vipashyana (Insight) Meditation:

- Calm the mind and establish clear shamatha first.

- Enter vipashyana meditation to develop insight

- Focus on the nature of sensory appearances (not just visual, but all) and the understanding that all phenomena arise as appearances within consciousness.

- Contemplation on Mind-Only: Contemplate the nature of mind and investigate all phenomena as ultimately mind-dependent. Seeing all experience as subjective, subsequently see the essence of mind.

Analytical Reflection on Chittamatra:

See the nature of perception, the distinction between conventional and ultimate, the role of consciousness in generating experience, and the implications for the nature of suffering and liberation.

Non-Dual Awareness: Chittamatra meditation transcends the experience of perceiver and perceived. A direct, non-conceptual seeing of the inseparability of mind and phenomena is the goal of Chittamatra – sherpa rang rig rang sol in Tibetan. Self-aware, self-illuminating mind: mind perceiving itself instead of external objects.

Process: Release thoughts of objects and look into and at the experiencer of those perceptions. Stabilize that looking with a gentle, relaxed focus. This meditation is not complicated, yet it is very difficult to actually do. The mind is used to looking outward and has little basis of experience to self-examine. A solid grounding in shamatha meditation, developing stable, clear focus on more substantive, outwardly appearing objects – statue, physical body, breath and so forth – until some degree of samadhi occurs is essential.

Through meditation on the sameness in substance of perception and perceiver, the 7th consciousness (afflicted or klesha) dissolves. This removes blockages to the self-illuminating mind, which then becomes the object of meditation.

Integration of Insights: Throughout the meditation practice, it is important to integrate the insights gained into one’s daily life and actions. The aim is to develop a deep understanding of the nature of mind and reality, which can transform one’s perception, thoughts, emotions, and behavior.

Key points: Chittamatra is NOT solipsism. Others exist and share your world. Chittamatra is saying the substance of reality is not different from mind itself. Inner perception and consciousness and outer objects are a single substance.

Svatantrika Madhyamika / Autonomy School and shunyata

Shunyata meaning in Buddhism is emptiness or voidness. This refers to relative reality in general.

Svatantrika, or Svatantrika-Madhyamaka, uses reasoning to refute the relative truth of mere appearance and establish emptiness, free of concept, as the absolute nature. Each category of phenomena is analyzed, found to be non-existent, and the mind rests in that empty experience.

All Madhyamaka systems aim to exhaust the reasoning mind, allowing ultimate truth to arise as direct experience. Reason exists in opposition to direct experience and must be released or it will interfere with meditation on ultimate reality.

The Svatantrika-Madhyamaka school was founded by the Indian philosopher Bhavaviveka. The term “Svatantrika” can be translated as “autonomous” or “independent.” Svatantrika Madhyamaka represents a distinct approach to the interpretation and presentation of Madhyamaka philosophy.

Svatantrika-Madhyamaka practitioners acknowledge the fundamental Madhyamaka view of the emptiness (shunyata) of all phenomena. They assert the relative truth that all phenomena lack inherent existence and are dependently arisen, meaning they arise due to causes and conditions.

However, Svatantrika-Madhyamaka introduces a nuanced perspective on the nature of ultimate reality and the way it is conventionally approached. It emphasizes the use of logical reasoning and the application of conventional truth to communicate the insights of emptiness effectively.

Key features and distinguishing characteristics of Svatantrika-Madhyamaka:

Two Levels of Truth: Svatantrika-Madhyamaka posits two levels of truth: conventional truth (samvriti-satya) and ultimate truth (paramartha-satya). While ultimate truth represents the ultimate reality of emptiness, conventional truth refers to the relative reality of conventional phenomena. Svatantrika emphasizes the importance of skillfully employing conventional language and concepts to communicate teachings effectively.

Prasaṅgika Methodology: Svatantrika-Madhyamaka incorporates the method of prasaṅga (consequence) argumentation, which involves establishing the logical consequences of an opponent’s position. It uses logical reasoning to expose the flaws and inconsistencies in the conceptual frameworks that assert inherent existence. Unlike Prasangika, Svatantrika positively asserts shunyata (emptiness) as the absolute, establishing emptiness through logical reasoning.

Use of Designation and Imputation: Svatantrika-Madhyamaka recognizes the importance of language and conceptual designation in conventional reality. It acknowledges that conventional phenomena are designated and imputed by conceptual mind, while still maintaining their ultimate emptiness.

Subtle Refutation: Svatantrika-Madhyamaka engages in a more subtle refutation of inherent existence compared to earlier Madhyamaka sub-schools. It presents arguments to undermine inherent existence without explicitly denying the conventional validity of the objects of negation. Another way of saying this: they go along with conventional appearances while maintaining the view of ultimate emptiness.

SVATANTRIKA MEDITATION

Always begin by taking refuge and, as this is a Mahayana practice, arousing bodhicitta.

Vipashyana (Insight) Meditation: Once the mind is settled through shamatha, engage in vipashyana meditation to cultivate insight into the nature of emptiness. In Svatantrika Madhyamaka, this involves analyzing the conventional nature of phenomena and investigating their emptiness. Reflect on the emptiness of the self, other people, objects, and all aspects of experience. This can be done by examining how things lack inherent existence and are dependently arise. Meaning: all phenomena arise temporarily from causes and continue due to conditions.

Analytical Reflection: Svatantrika-Madhyamaka emphasizes the use of logical reasoning and critical analysis. During meditation, you can engage in analytical reflection on the nature of conventional truth and ultimate truth. Contemplate the relationship between language and concepts and their ability to convey both conventional and ultimate realities. Reflect on how designation and imputation function in conventional reality while acknowledging the ultimate emptiness of phenomena.

Questioning and Inquiry: Svatantrika encourages a spirit of inquiry and investigation. During meditation, you can pose questions to yourself and engage in introspection. For example, ask yourself, “What is the nature of this self that I normally assume to exist inherently?” or “How does the appearance of inherent existence arise in my experience?” Then investigate and analyze these questions with a keen sense of curiosity.

During formal meditation, you should practice until definite experience arises on each stage. At that point, don’t go back to analysis. Instead rest in the experience of emptiness, at whatever stage, completely relaxed, without wandering.

PRASANGIKA

Prasangika, or Consequence School, of emptiness, utilizes powerful logics to overturn any positively stated assertions. This refutes all conventional truth and absolute truths, even in other Buddhist schools. No positive assertions are made in Prasangika.

The Prasangika view is considered the most refined and definitive presentation of Madhyamaka philosophy. The key features and view of Prasangika-Madhyamaka include:

Emptiness and Dependent Arising: Prasangika-Madhyamaka emphasizes that all phenomena lack inherent existence and are empty of inherent, independent existence. It asserts that all things arise dependently based on causes and conditions and are devoid of any inherent, separate essence. Emptiness is not a separate entity but the ultimate nature of all phenomena.

Two Truths in Buddhism

Prasangika-Madhyamaka acknowledges the two levels of truth: conventional truth (samvriti-satya) and ultimate truth (paramartha-satya). Conventional truth refers to the relative, conventional reality, while ultimate truth refers to the ultimate nature of reality, which is emptiness. Prasangika-Madhyamaka asserts that conventional truth is not negated by the realization of emptiness.

Consequence-Based Reasoning: Prasangika-Madhyamaka relies on prasaṅga, or consequence-based reasoning, to demonstrate the untenability of any position that asserts inherent existence. Instead of asserting positive statements about the ultimate nature of reality, Prasangika-Madhyamaka engages in a reductio ad absurdum approach. It shows the logical inconsistencies and contradictions that arise if inherent existence were accepted.

Refutation of Inherent Existence: Prasangika-Madhyamaka refutes inherent existence by demonstrating that all phenomena are dependent and designated. It argues that inherent existence is a conceptual construct, a mistaken imputation onto phenomena. Phenomena appear conventionally but lack any intrinsic essence or self-nature.

Conventional Validity: Prasangika-Madhyamaka upholds the conventional validity of all phenomena, despite their ultimate emptiness. It recognizes the functional and conventional reality of phenomena within the framework of dependent arising and conventional designations.

Non-Affirming Negation: Prasangika-Madhyamaka employs the technique of non-affirming negation. Instead of asserting something positive about the nature of reality, it negates inherent existence while refraining from positing any alternative ontological claims. This approach avoids falling into the extremes of nihilism or substantialism.

The Prasangika view is considered the pinnacle of Madhyamaka philosophy and has been particularly influential in Tibetan Buddhism. Scholars such as Nagarjuna, Chandrakirti, and Tsongkhapa have contributed significantly to the development and elucidation of Prasangika-Madhyamaka teachings.

PRASANGIKA MEDITATION

Take refuge, arouse Bodhicitta, and settle the mind through shamatha.

Vipashyana (Insight) Meditation: Once the mind is settled through shamatha, engage in vipashyana meditation to develop insight into the nature of emptiness. In Prasangika-Madhyamaka, this involves examining the conventional nature of phenomena and investigating their emptiness. Reflect on the interdependence and lack of inherent existence in your own experiences and the objects of your perception. Explore the emptiness of the self, others, and all phenomena.

Analytical Reflection: Prasangika-Madhyamaka encourages critical analysis and logical reasoning. During meditation, engage in analytical reflection on the nature of emptiness and inherent existence. Contemplate the consequences of asserting inherent existence and the logical inconsistencies that arise. Investigate the conventional designation of phenomena and their ultimate emptiness.

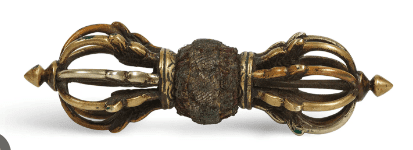

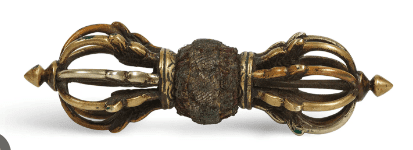

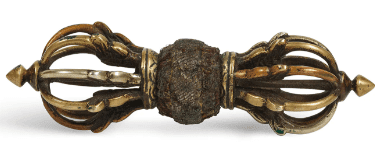

Study Madhyamaka philosophy and argumentation. Especially master the arguments of the One and the Many and the Tiny Vajra – these key logics overcome fixed ideas of existence about solid objects and causality. Avoid the belief in nihilism as this is a trap. Understand the meaning of Freedom from the four Extremes of existence, non-existence, both, and neither.

Non-Dual Awareness: Prasangika-Madhyamaka emphasizes the non-dual nature of conventional and ultimate reality. Cultivate non-dual awareness by letting go of conceptual elaborations and directly experiencing the interdependent and empty nature of phenomena. Rest in a state of non-conceptual awareness, allowing the conventional appearances of phenomena to arise and dissolve without grasping onto inherent existence.

SHENTONG

Shentong means Empty of Other, or the ultimate nature possesses a self-essence, but has no qualities associated with the relative. It emphasizes Rigpa, the luminous-empty essence of awareness as the meditative path to realization.

The view of Shentong, which is associated with the Jonang school of Tibetan Buddhism, is a philosophical perspective that emphasizes the ultimate reality of the mind and the nature of ultimate truth. Here are the key aspects and characteristics of the Shentong view:

Other-Emptiness:

Shentong emphasizes the concept of “other-emptiness” or “empty of other.” It posits that the ultimate nature of reality, specifically the ultimate nature of the mind or consciousness, is empty of all that is other than its own luminous nature. This means that the mind has an inherent luminosity or Buddha nature that is unconditioned and not dependent on external factors.

Inherent Luminosity

Shentong asserts that the mind, at its ultimate nature, possesses an inherent luminosity or clarity that is beyond conceptual elaboration and defilements. This luminosity is seen as the ground of awakening and the basis for realizing enlightenment. It is considered to be a pure and radiant essence that is not affected by temporary afflictions or obscurations. Importantly, luminosity is empty also – empty of physicality/materiality, empty of conceptual elaboration, empty of all impurities or stains.

Buddha Nature

Shentong teaches that all sentient beings possess an innate Buddha nature, which is the potential for enlightenment. This Buddha nature is seen as the luminous and awakened aspect of the mind, capable of fully realizing its own nature. It is regarded as the ultimate basis for the development of wisdom and compassion. Where Prasangika proceeds from the Second Turning of the Wheel of Dharma, Shentong is based on the Third Turning.

Yogic Direct Perception

Shentong emphasizes the importance of direct meditative experience as a means to directly realize the ultimate nature of mind and its inherent luminosity. It encourages practitioners to engage in meditation practices that allow for the direct perception of the luminous nature of mind, leading to a direct realization of its ultimate reality.

Unity of Emptiness and Luminosity: Shentong views emptiness and luminosity as inseparable and non-dual. While conventional reality is characterized by emptiness, the ultimate reality of the mind is understood as both empty and inherently luminous. This unity of emptiness and luminosity is seen as the true nature of reality.

SHENTONG MEDITATION

Vipashyana (Insight) Meditation: Once the mind is settled through shamatha, engage in vipashyana meditation to develop insight into the nature of the mind. In Shentong, this involves turning the attention inward and investigating the luminous and clear nature of the mind itself. Observe the arising and passing of thoughts, emotions, and sensations, recognizing their empty and transient nature. Rest in the pure awareness that underlies all mental activity.

Direct Perceptual Meditation: “Look at that which produces the thoughts. Look at the watcher itself.” Shentong emphasizes the direct perception of the luminous nature of the mind. Engage in meditation practices that allow for direct experience and realization of this luminosity. This may involve techniques such as Dzogchen’s rigpa or Mahamudra’s “pointing-out instruction,” where a qualified teacher points directly to the nature of mind, facilitating direct perception and recognition of its inherent luminosity.

Shentong meditation corrects the Rangtong error to over-negate. Through this process of subtle negation of all experience as not truly existent, the Rangtongpa subtly negates the experience of actual awareness, or Rigpa, unintentionally creating a final obstacle to non-dual enlightenment.

What does emptiness mean in Buddhism?

Emptiness or shunyata means lacking inherent existence as a singular, permanent, self-existing entity.

What is the principle of emptiness?

The principle of emptiness is non-essence or no fixed core identity to phenomena.

What is emptiness the most misunderstood word in Buddhism?

Shunyata is the explanation for the relative essence of reality, which has no stable, discernable qualities.

What is the empty void in Buddhism?

It is shunyata, the essential characteristic of reality as perceived by conventional mind. Essencelessness.

Is emptiness nothingness in Buddhism?

Emptiness or sunyata in Buddhism is not ‘nothingness,’ as that would be nihilism, one of the two extremes. It is essencelessness or identitylessness.

Is life meaningless according to Buddhism?

Life is not meaningless in Buddhism. However, the struggle to succeed in samsara is meaningless. Having compassion for sentient beings and engaging in the quest for wisdom are tremendously meaningful.

May all beings be happy

May all beings be peaceful

May all beings be safe

May all beings awaken to the light of their true nature

May all beings be free