Koans (gōng’àn in Chinese) are non-logical semantic constructs (stories, statements, etc) intended to push students into the initial insight of dharma mind, then through the initial arrogance accompanying that insight.

My understanding of koan in Zen Buddhism is that is meant to ‘stop’ the mental process. We focus on the koan in meditation, until at some point, our mind finds nothing to grasp onto. A teacher says something that doesn’t quite make sense. When we meditate on it, our logical mind tries to figure it out. I find this is challenging, just to stay on such an object. However, when we do achieve concentration on the koan, we cannot penetrate it meaningfully, because it has no real meaning. It is pseudo-meaningful. This engages the intellect because thinking mind likes to solve puzzles.

But koan is no puzzle, only the illusion of a puzzle. I may experience frustration, or some flickers of insight, but the deeper meaning of the puzzle eludes me. Why wouldn’t it? It isn’t there. Eventually, my mind exhausts its attempts and just stops trying. Then – satori, an enlightenment experience.

Based on this experience, the ego arises to claim it. We don’t notice because, well, we have seen something real. The insight was valid. Now we need to deal with that neurosis. The koan then is practiced to reveal to ego, that there was no insight. There was nothing to get in actuality, so ego has no place to hang its pride.

Table of Contents

Secrets of Meditation for Anxiety

Like millions of people, you may have suffered from anxiety for years. Meditation, yoga, peaceful music – it never works. It takes too long, and it’s not stable. Why? Because peace is treated as a cause for freedom, but it’s not – it’s the result. The cause to free yourself from anxiety is completely different.

Click now to Overcome Anxiety for good.

Koan Summary

Central Entity: Koan

Category: Zen Buddhist Teaching Tool (Primarily Rinzai Zen)

Description: A koan is a paradoxical riddle or statement used in Zen Buddhist training to challenge logical thinking and promote a deeper understanding of reality beyond the limitations of the intellect.

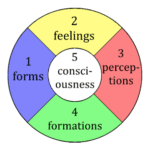

Purpose:

- To break through conceptual thinking and lead to a direct experience of enlightenment (kensho).

- To challenge students to abandon reliance on reason and logic and embrace a more intuitive way of knowing.

- To cultivate a state of “mu” (non-mind) where the duality of subject and object dissolves.

Characteristics:

- Paradoxical: Koans are seemingly nonsensical or contradictory statements that cannot be solved through intellectual reasoning.

- Open-ended: Koans have no single, definitive answer. The student must grapple with the koan through meditation and introspection.

- Provocative: Koans are designed to create confusion and frustration, ultimately leading to a breakthrough in understanding.

Example:

- “What is the sound of one hand clapping?”

How Koans Work:

- A Zen master presents a koan to a student.

- The student contemplates the koan for days, weeks, or even months, seeking a logical solution.

- Through meditation and introspection, the student eventually experiences an intuitive understanding that transcends logic.

Benefits:

- Deepens insight into the nature of reality

- Cultivates a state of “mu” (non-mind)

- Promotes a more intuitive way of knowing

- Fosters self-reflection and critical thinking

Limitations:

- Koans can be frustrating and discouraging for beginners.

- The emphasis on non-rationality can be off-putting to some individuals.

- Koan study is best undertaken under the guidance of a qualified Zen master.

Related Concepts:

- Zen Buddhism (particularly Rinzai Zen)

- Zazen Meditation

- Enlightenment (kensho)

- Mu (non-mind)

- Zen Masters

Additional Notes:

- Koans are a unique and challenging aspect of Zen Buddhist training.

- They are not meant to be solved intellectually, but rather to be contemplated and experienced on a deeper level.

How to meditate like a yogi

and enter profound samadhi

List of Koans

From The Gateless Gate

Koan: Joshu’s Dog

A monk asked Jōshū in all earnestness, “Does a dog have Buddha nature or not?”

Jōshū said, “Mu!”

MUMON’S COMMENTARY

For the practice of Zen, you must pass the barrier set up by the ancient patriarchs of Zen. To attain to marvelous enlightenment, you must completely extinguish all thoughts of the ordinary mind. If you have not passed the barrier and have not extinguished all thoughts, you are a phantom haunting the weeds and trees. Now, just tell me, what is the barrier set up by the patriarchs? Merely this Mu—the one barrier of our sect. So it has come to be called “The Gateless Barrier of the Zen Sect.” (the original koan)

Those who have passed the barrier are able not only to see Jōshū face to face but also to walk hand in hand with the whole descending line of patriarchs and be eyebrow to eyebrow with them. You will see with the same eye that they see with, hear with the same ear that they hear with. Wouldn’t it be a wonderful joy? Isn’t there anyone who wants to pass this barrier? Then concentrate your whole self into this Mu, making your whole body with its 360 bones and joints and 84,000 pores into a solid lump of doubt.

Day and night, without ceasing, keep digging into it, but don’t take it as “nothingness” or as “being” or “non-being.” It must be like a red-hot iron ball which you have gulped down and which you try to vomit up but cannot. You must extinguish all delusive thoughts and beliefs which you have cherished up to the present. After a certain period of such efforts, Mu will come to fruition, and inside and out will become one naturally. You will then be like a dumb man who has had a dream. You will know yourself and for yourself only.

Then all of a sudden, Mu will break open. It will astonish the heavens and shake the earth. It will be just as if you had snatched the great sword of General Kan: If you meet a Buddha, you will kill him. If you meet a patriarch, you will kill him. Though you may stand on the brink of life and death, you will enjoy the great freedom. In the six realms and the four modes of birth, you will live in the samadhi of innocent play.

Now, how should you concentrate on Mu? Exhaust every ounce of energy you have in doing it. And if you do not give up on the way, you will be enlightened the way a candle in front of the altar is lighted by one touch of fire.

Koan: Tesho on the Case

THE CASE

Whenever Master Hyakujō delivered a sermon, an old man was always there listening with the monks. When they left, he left too. One day, however, he remained behind. The master asked him, “What man are you, standing in front of me?” The old man replied, “Indeed, I am not a man. In the past, in the time of Kashyapa Buddha,1 I lived on this mountain (as a Zen priest). On one occasion a monk asked me, ‘Does a perfectly enlightened person fall under the law of cause and effect or not?’

I answered, ‘He does not.’ Because of this answer, I fell into the state of a fox for 500 lives. Now, I beg you, Master, please say a turning word2 on my behalf and release me from the body of a fox.” Then he asked, “Does a perfectly enlightened person fall under the law of cause and effect or not?”

The master answered, “The law of cause and effect cannot be obscured.” Upon hearing this, the old man immediately became deeply enlightened. Making his bows, he said, “I have now been released from the body of the fox and will be behind the mountain. I dare to make a request of the Master. Please perform my funeral as you would for a deceased priest.”

The master had the Ino3 strike the anvil4 with a gavel and announce to the monks that after the meal there would be a funeral service for a deceased priest. The monks wondered, saying, “All are healthy. No one is sick in the infirmary. What’s this all about?” After the meal, the master led the monks to the foot of a rock behind the mountain and with his staff poked out the dead body of a fox. He then performed the ceremony of cremation.

That evening the master ascended the rostrum in the hall and told the monks the whole story. Ōbaku thereupon asked, “The man of old missed the turning word and fell to the state of a fox for 500 lives. Suppose every time he answered he made no mistakes, what would happen then?” The master said, “Just come nearer and I’ll tell you.” Ōbaku then went up to the master and slapped him. The master clapped his hands and, laughing aloud, said, “1 thought the barbarian’s beard was red, but here is a barbarian with a red beard!”

Koan: Gutei’s One Finger

Whatever he was asked about Zen, Master Gutei simply stuck up one finger.

He had a boy attendant whom a visitor asked, “What kind of teaching does your master give?” The boy held up one finger too. Hearing of this, Gutei cut off the boy’s finger with a knife. As the boy ran away, screaming with pain, Gutei called to him. When the boy turned his head, Gutei stuck up one finger. The boy was suddenly enlightened.

When Gutei was about to die, he said to the assembled monks, “I received this one-finger Zen from Tenryū.1 I’ve used it all my life but have not exhausted it.” Having said this, he entered nirvana.

MUMON’S COMMENTARY

The enlightenment of Gutei and the boy have nothing to do with the tip of a finger. If you realize this, Tenryū, Gutei, the boy, and you yourself are all run through with one skewer.

THE VERSE

Old Tenryū made a fool of Gutei,

Who cut the boy with a sharp blade.

The mountain deity Korei raised his hand, and lo, without effort,

Great Mount Ka with its many ridges was split in two!

The Barbarian Has No Beard

Wakuan said, “Why has the western barbarian no beard?”

MUMON’S COMMENTARY

If you practice Zen, you must actually practice it. If you become enlightened, it must be the real experience of enlightenment. You see this barbarian once face to face; then for the first time, you will be able to acknowledge him. But if you say that you see him face to face, in that instant there is division into two.

Koan: Kyōgen’s Man Up a Tree

Master Kyōgen said, “It’s like a man up a tree, hanging from a branch by his mouth; his hands cannot grasp a branch, his feet won’t reach a bough. Suppose there is another man under the tree who asks him, ‘What is the meaning of Bodhidharma’s coming from the west?’ If he does not respond, he goes against the wish of the questioner. If he answers, he will lose his life. At such a time, how should he respond?”

MUMON’S COMMENTARY

Even if your eloquence flows like a river, it is of no use. Even if you can expound the whole body of the sutras, it is of no avail. If you can respond to it fittingly, you will give life to those who have been dead, and put to death those who have been alive. If, however, you are unable to do this, wait for Maitreya to come and ask him.

THE VERSE

Kyōgen is really absurd,

His perversity knows no bounds;

He stops up the monks’ mouths,

Making his whole body into the glaring eyes of a demon.

Koan: Buddha Holds Up a Flower

Once in ancient times, when the World-Honored One was at Mount Grdhrakūta,1 he held up a flower, twirled it, and showed it to the assemblage.

At this, they all remained silent. Only the venerable Kashyapa broke into a smile.

The World-Honored One said: “I have the eye treasury of the true Dharma, the marvelous mind of nirvana, the true form of no-form, the subtle gate of the Dharma. It does not depend on letters, being specially transmitted outside all teachings. Now I entrust Mahakashyapa with this.”

MUMON’S COMMENTARY

The golden-faced Gautama insolently suppressed noble people and made them lowly. He sells dog’s flesh under the label of sheep’s head. I thought there should be something of particular merit in it. If at that time, however, all those attending had smiled, how would the eye treasury of the true Dharma have been transmitted? Or if Kashyapa had not smiled, how would he have been entrusted with it?

If you say that the eye treasury of the true Dharma can be transmitted, then that is as if the golden-faced old man is swindling country people at the town gate. If you say it cannot be transmitted, then why did Buddha say he entrusted only Kashyapa with it?

THE VERSE

In handling a flower,

The tail of the snake manifested itself.

Kashyapa breaks into a smile,

Nobody on earth or in heaven knows what to do.

More Koans

Master Gettan asked a monk, “Keichū made a hundred carts. If he took off both wheels and removed the axle, what would he make clear about the cart?”

When Tōzan came to Unmon for instruction, Unmon asked, “Where have you come from?” Tōzan said, “From Sado.” Unmon said, “Where were you during the summer retreat?” Tōzan said, “At Hōzu Monastery, south of the lake.” Unmon said, “When did you leave there?” Tōzan said, “On the twenty-fifth of August.” Unmon said, “I spare you sixty blows.”

The next day Tōzan came up to Unmon and asked, “Yesterday you spared me sixty blows though I deserved them. I beg you, sir, where was I at fault?” Unmon said, “Oh, you ricebag! Have you been wandering about like that, now west of the river, now south of the lake?” At this, Tōzan had great realization.

Once the monks of the eastern and western Zen halls in Master Nansen’s temple were quarrelling about a cat. Nansen held up the cat and said, “You monks! If one of you can say a word, I will spare the cat. If you can’t say anything, I will put it to the sword.” No one could answer, so Nansen finally slew it. In the evening when Jōshū returned, Nansen told him what had happened. Jōshū thereupon took off his sandals, put them on his head, and walked off. Nansen said, “If you had been there, I could have spared the cat.”

A monk once asked Unmon, “The radiance serenely illuminates the whole vast universe . . .” Before he could finish the first line, Unmon suddenly interrupted, “Aren’t those the words of Chōsetsu Shūsai?” The monk replied, “Yes, they are.” Unmon said, “You have slipped up in the words.”

Afterwards, Zen Master Shishin brought the matter up and said, “Tell me, at what point did he slip?”

Goso said, “For example, it’s just like a great cow passing through a latticed window. Her head, horns, and four legs have passed through. Why is it that her tail can’t pass through?”

A monk asked Master Kempō in all earnestness, “In a sutra it says, ‘Ten-direction Bhagavats, one Way to the gate of nirvana.’ I wonder where the Way is.” Kempō lifted up his stick, drew a line and said, “Here it is.”

A monk asked Baso in all earnestness, “What is Buddha?” Baso replied, “No mind, no Buddha.”

Later a monk asked Unmon to give instruction about this. Unmon held up his fan and said, “This fan jumps up to the heaven of the thirty-three devas and adheres to the nose of the deva Taishaku. When a carp in the eastern sea is struck with a stick, it rains torrents as though a tray of water is overturned.”

Master and Patriarch En of Tōzan said, “Even Shakyamuni and Maitreya are servants of that one. Just tell me, who is that one?”

Master Bashō said to the assembly, “If you have a shujō, I will give it to you. If you have no shujō, I will take it away from you.”

A monk asked Nansen in all earnestness, “Is there any Dharma that has not been preached to the people?” Nansen said, “There is.” The monk said, “What is the Dharma which has never been preached to the people?” Nansen said, “This is not mind; this is not Buddha; this is not a thing.”

Bodhidharma sat facing the wall. The second patriarch, standing in the snow, cut off his arm and said, “Your disciple’s mind is not yet at peace. I beg you, Master, give it rest.” Bodhidharma said, “Bring your mind to me and I will put it to rest.”

Taibai asked Baso in all earnestness, “What is Buddha?” Baso answered, “The very mind is Buddha.”

Jōshū earnestly asked Nansen, “What is the Way?” Nansen answered, “The ordinary mind is the Way.” Jōshū asked, “Should I direct myself toward it or not?” Nansen said, “If you try to turn toward it, you go against it.” Jōshū asked, “If I do not try to turn toward it, how can I know that it is the Way?”

Nansen answered, “The Way does not belong to knowing or not-knowing. Knowing is delusion; not-knowing is a blank consciousness. When you have really reached the true Way beyond all doubt, you will find it as vast and boundless as the great empty firmament. How can it be talked about on a level of right and wrong?” At these words, Jōshū was suddenly enlightened.

The patriarch said, “I have searched for the mind but have never been able to find it.” Bodhidharma said, “I have finished putting it to rest for you.”

A non-Buddhist in all earnestness asked the World-Honored One, “I do not ask about words, I do not ask about no-words.” The World-Honored One just sat still. The non-Buddhist praised him, saying, “The World-Honored One in his great benevolence and great mercy has opened the clouds of my delusion and enabled me to enter the Way.” Then, bowing, he took his leave. Ananda asked Buddha, “What did the non-Buddhist realize that made him praise you so much?” The World-Honored One replied, “He is just like a fine horse that runs even at the shadow of a whip.”

Nansen said, “Mind is not Buddha; knowing is not the Way.”

May all beings be happy

May all beings be peaceful

May all beings be safe

May all beings awaken to the light of their true nature

May all beings be free